This is the third article about git on this blog. It is highly recommended to read the other two as well: there is one about some good practices in using git and another one about some aliases which will speed up your interaction with the commit history.

The series of articles about git continues with a short presentation about two other aliases and the reason why they should be used in order to create better commits.

Rebase instead of merge

From time to time we rush to push our changes to the remote repository without thinking of the possibility that another developer had made some commits in the meantime. Luckily, we are announced when this happens:

mihai@keldon:/data/ROSEdu/techblog$ git push

To gitolite@git.rosedu.org:techblog.git

! [rejected] contrib -> contrib (non-fast-forward)

error: failed to push some refs to 'gitolite@git.rosedu.org:techblog.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the tip of your current branch is behind

hint: its remote counterpart. Merge the remote changes (e.g. 'git pull')

hint: before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.What is a fast-forward update? What we tried to do in the above command was just to update one reference in the upstream repository: we wanted to change the HEAD reference which pointed to a commit – let’s call it A – to another commit, the latest one in our repository – let’s call it B.

If and only if B is a descendant of A we have a fast-forward update. Otherwise, the update is non-fast-forward. These definitions generalize to local branches or any other kind of reference updates.

What is the purpose of this distinction? Any fast-forward updated guarantees that the history of both branches is not lost. In contrast, a non-fast-forward update will certainly lose a part of the history.

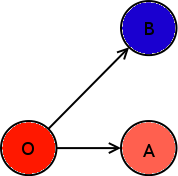

We need to change our point of view to see this. Let us view the two repositories in a simple diagram showing both branches from the very moment when the local repository was cloned:

The HEAD reference for the remote repository was pointing at commit A and we want to make it to point at commit B which is not a direct descendent of A, thus the update is non-fast-forward.

If git push was allowed to finish successfully in any of the two cases then the history from O up to A would be lost: developers would only see the history from O to B and would work only on top of the B commit. This is why git push failed.

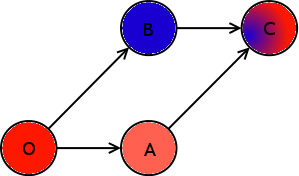

The error message suggests to do a git pull in order to merge the two branches. Let’s see what will happen when we do this:

A merge commit C was created containing changes from both A and B. This is a new commit and it looks like the following one:

mihai@keldon:$ git show 2603167

commit 2603167229a11b8dad6715246041ad29f792308c

Merge: ad4d7a1 6091ae3

Author: Alex Juncu <ajuncu@ixiacom.com>

Date: Wed Nov 30 15:32:05 2011 +0200

Merge branch 'contrib' of git.rosedu.org:techblog into contribThere are cases where this merge commit is needed. However, not all instances of the above diagram need a merge commit.

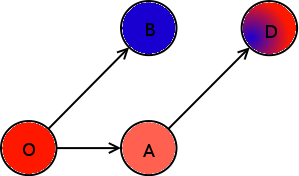

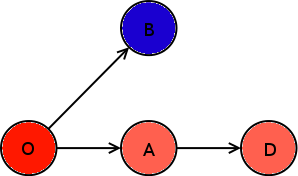

The other alternative is to do a rebase first using git pull --rebase for example. In this case, the following thing will happen: a new commit D will be created containing the set of changes needed to be applied on top of A in order to reach B.

Now, the D commit is already on top of A and the push will be a fast-forward update. This can be seen from the following screen as well:

mihai@keldon:$ git pull --rebase

remote: Counting objects: 5, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From git.rosedu.org:techblog

b557977..38da5d0 contrib -> origin/contrib

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: Add author for first article.The push will simply update the HEAD reference to point to the D commit.

If the rebase cannot be done because of a merge conflict we are announced of this and the rebase will stop until we resolve it.

There are several ways to make git try to always use --rebase when pulling. What I recommend is to create an alias. I have this in ~/.gitconfig:

[alias]

gpr = pull --rebaseThis has two benefits: I always try to do a rebase first and I type less. In fact, using TAB completion I have to press only 5 keys for this.

Interactive addition of changes

One rule for better git commits is to have short and meaningful commits with relevant commit messages. However, it is possible that we have done several unrelated changes to a single file (for example we have updated a comment and added some new code). Issuing a simple git add file will break the above rule.

One solution for this is to use git add --interactive. It is better to use git add --patch though.

Our change will be split in several hunks and each of them will be offered to us with a simple question at the end:

@@ -76,6 +78,10 @@ TODO

Did you mean this?

gpr

+TODO: git gdc

+

+TODO: final thoughts

+

[git]: http://git-scm.com/ "Git"

[ggp]: http://techblog.rosedu.org/git-good-practices.html "Git good practices"

[gsw]: http://techblog.rosedu.org/git-speeding-workflow.html "Git speeding workflow"

Stage this hunk [y,n,q,a,d,/,K,g,e,?]? yWe can decide to accept or reject the hunk for this commit or we can split it in several other hunks. We can even edit the hunk if we need this.

In order to speed up typing I have an alias for this as well:

gap = add --patchI have imprinted in my muscle memory to never type git add but git gap.

Conclusions

The two aliases presented above help us be a little more proficient with git usage. I have been using them for several months now and the results are good.