In every programmer’s life there comes a time when he has to leave the realm of integers and tread into the dangerous land of rational numbers. He/she might do some scientific computation, or work on a financial application or a game rendering pipeline or even in some artificial intelligence or data-mining algorithm – in all of these cases and many others, restricting oneself to using only integers is no longer feasible.

And, as soon as one starts using floating point a lot of interesting things happen, starting from results which don’t show up nicely and bad equality testing and going towards subtler and subtler bugs.

Even experts and common-sense is at fault in this realm. For example, did you know that always comparing two floating points like in the following code is bad?

if (fabs(a - b) < 0.0001)

do_something_with_equal_numbers(a);Without being a complete guide, this article shows some of the beauties and dangers of the floating-point realm.

A common pitfall

Beginners programmers expect floating point number to act as the real fractional numbers: no errors involved. Slightly experienced programmers know that this is not the case, yet even the most careful and experienced ones make mistakes from time to time. We will focus more on the common pitfalls and not on the occasional mistreatments given by experts.

For example, someone unprepared might write the following code

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main ()

{

float a = 0.1;

float b = 0.2;

float c = a + b;

if (c != 0.3)

printf("%f\n%f\n%f\n%f\n", c, a + b, 3 * a, 1.5 * b);

return 0;

}and be surprised to see that results are

$ ./a.out

0.300000

0.300000

0.300000

0.300000Note: Your results on your machine might vary. Later in the article we will discuss this aspect at length.

Of course, the problem in here is pretty simple: all floating point constants use double precision thus the code should at least read

if (c != 0.3f)

printf(...)I say at least because even if on my architecture I got the exact value of 0.3, this is not the case on all of them. Why? Because none of the 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 values have an exact representation in base 2. One can see that by trying to convert the number into base 2. Let’s follow the example of 0.3:

- the integral part of

0.3is0so it is also in base 2 - double the number, we get

0.6, its integral part is0thus the first binary digit after decimal point of0.3is still a0. - double this result, we get

1.2so the next digit is a1and we are left with0.2 - double it, get

0.4, next binary digit is0 - double it, get

0.8, next binary digit is0 - double it, get

1.6, next binary digit is1and we’re back to0.6

Thus, the binary representation of 0.3 would be 0.01001100110011001... Repeating the same algorithm with 0.1 and 0.2 will end in the same loop between 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 0.6. So, none of 0.1, 0.2 or 0.3 has an exact representation. Thus, no result of any operation with these numbers will be an exact answer.

But, then, why did we get the exact answer in here? The two sensible answers are that either the compiler generates code which uses a higher level of precision than the space reserved for float or the printing routine does hard work to properly display the numbers. We can test these hypotheses using gdb:

$ gdb -q ./a.out

Reading symbols from /tmp/fps/a.out...done.

(gdb) b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x400538: file 1.c, line 6.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /tmp/fps/a.out

Breakpoint 1, main () at 1.c:6

6 float a = 0.1;

(gdb) n

7 float b = 0.2;

(gdb) p a

$1 = 0.100000001

(gdb) n

8 float c = a + b;

(gdb) p b

$2 = 0.200000003As you can see, printing the values from memory shows that they are not 0.1 and 0.2 but values close to that.

Let’s see now what the assembly code around c = a + b looks like:

(gdb) disass

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000400530 <+0>: push %rbp

0x0000000000400531 <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x0000000000400534 <+4>: sub $0x10,%rsp

0x0000000000400538 <+8>: mov 0x142(%rip),%eax # 0x400680

0x000000000040053e <+14>: mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

0x0000000000400541 <+17>: mov 0x13d(%rip),%eax # 0x400684

0x0000000000400547 <+23>: mov %eax,-0x8(%rbp)

=> 0x000000000040054a <+26>: movss -0x4(%rbp),%xmm0

0x000000000040054f <+31>: addss -0x8(%rbp),%xmm0

0x0000000000400554 <+36>: movss %xmm0,-0xc(%rbp)

---Type <return> to continue, or q <return> to quit---q

QuitThe last three lines are the assembly lines generated for float c = a + b (you can test that by running an objdump -CDgS | less and searching for float c). -0x4(%rbp) is where a is stored on the stack. b is stored at -0x8(%rbp). The assembly instructions used – addss and movss – and the register involved – xmm0 – show that we are working with Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE). This register has a precision of 128 bits which is 4 times greater than the 32 bits used by the float datatype. We are tempted now to think that we are able to use the full width of the register – even if the SIMD part of the extension tells that this is not the case, we want a real proof based on the memory/register contents.

Continuing the execution, we see:

(gdb) n

9 if (c != 0.3)

(gdb) p $xmm0

$3 = {v4_float = {0.300000012, 0, 0, 0}, v2_double = {5.18894283457103e-315,

0}, v16_int8 = {-102, -103, -103, 62, 0 <repeats 12 times>}, v8_int16 = {

-26214, 16025, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}, v4_int32 = {1050253722, 0, 0, 0}, v2_int64 =

{1050253722, 0}, uint128 = 1050253722}

(gdb) p c

$4 = 0.300000012Indeed, our c is not 0.3. But it seems that not even the contents of xmm0 are closer to the truth.

So, the fact that we got 0.3 in the output is caused not by the fact that we use a 128-bits wide registers but by the fact that the up-to-recent unsolved problem of precisely printing floating point numbers is no longer so.

The floating point standard

Before we further investigate the realm of floating points, let’s have a look at the standard used for storing and working with these numbers: IEEE-754. We would not go in full details since we are only interested in some minor aspects.

First of all, the standard defines the way in which we can store a floating point number as three integer numbers: one for the sign (which is always 0 or 1), one for an exponent which gives us access to a wider range than[0..2^32] and one for the mantissa. The final number is just the product of the mantissa, the base (2 in case of binary numbers, 10 in case of decimal numbers – the standard defines some way to store decimal numbers too) raised to the exponent power and (-1) raised to the sign value.

Depending on the sizes of these numbers we have the basic float type (or binary32) in which the total size of the three numbers is 32 bits. In this case 1 bit is reserved for the sign, 8 for the exponent and the other 23 for the mantissa.

The C double type is defined by the binary64 format: 1 bit of sign, 11 bits for the exponent and 52 bits for the mantissa for a total of 64. There is also a binary128 format and a C long double type. In this case 15 bits are reserved for the exponent and 112 for the mantissa.

The standard committee has come up with a clever idea of storing these numbers into binary format. For example, they don’t store the exponent in 2’s complement but modified via an offset. Thus, the bit patterns of two nearby representable floats represent two consecutive integer values. This allows us to do some interesting tricks with the two representations of real numbers.

The standard also defines \(\infty\) and \(-\infty\), two values for 0 (+0 and -0 and how they should be tested equal but treated differently in operations) and a full sequence of values which don’t represent a number but some exception – the sometimes dreaded NaN values.

Knowing these details about the IEEE-754 standard we can go forward in our exploration. Because from now on we would use the binary representation and won’t rely on the base 10 view of numbers we will use an online analyzer to investigate interesting values.

Back to the castle and a final conclusion

Returning to our code, we want to see what values are stored in memory for a, b and c and also in register xmm0:

(gdb) x $rbp - 0x4

0x7fffffffdfac: 0x3dcccccd

(gdb) x $rbp - 0x8

0x7fffffffdfa8: 0x3e4ccccd

(gdb) x $rbp - 0xc

0x7fffffffdfa4: 0x3e99999a

(gdb) p/x $xmm0

$4 = {.... uint128 = 0x0000000000000000000000003e99999a}Looking through the analyzer, 0x3dcccccd (the value for a) is 1.00000001490116119384765625E-1 which is both close to the original value of 0.1 and to the displayed value of 0.100000001. Same for b and c. However, looking at xmm0 register we see that the last 32 bits have the same pattern as -0xc($rbp). Thus, the SSE 128 bits registers are not using the binary128 standard! If they were using it, the last value displayed there should have been 3FFD3333333333333333333333333333. As said on reddit thread for this article, excess precision comes from the x87 coprocessor which uses 80 bits of precision.

Now it is time to see some other aspects of working with floating point numbers.

Testing them all

Since there is a perfect isomorphism between float values and int ones and there are only 2^32 ints (on normal architectures), sometimes it is easy and desirable to test a new function on all of the possible values. Unfortunately, this doesn’t properly work for functions with more than one argument because one would have to spend ages for that. But for one single argument things are pretty nice: it only takes 16 seconds on my machine to run the following code which tests that changing the sign twice gives the same value:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main()

{

unsigned int i = 0;

float x;

do {

x = *((float*)&i);

if (x != -(-x))

printf("%f %u\n", x, i);

i++;

} while (i != 0);

return 0;

}Running it we see:

$ gcc -Wall -Wextra -O0 -g 2.c

$ ./a.out | head -n 5

nan 2139095041

nan 2139095042

nan 2139095043

nan 2139095044

nan 2139095045It seems that our hypothesis fails when the initial number was a NaN value. For now, let us filter all of these values and test the hypothesis on the remaining domain.

$ time ./a.out | grep -v nan

real 0m15.895s

user 0m17.977s

sys 0m0.163sSomething which we would have expected.

Note: Compiling with optimisations on might make the compiler issue the following warning:

warning: dereferencing type-punned pointer will break strict-aliasing rules [-Wstrict-aliasing]

^This is because the C/C++ standard says that the compiler can assume that different types don’t overlap in memory so neither should pointers to those types. Knowing that a pointer to an array of integers and one array of doubles don’t overlap opens a way for some optimizations. Breaking them is at your own risk. See also the documentation for -fstrict-aliasing flag of gcc.

The NaN problem

You might be wondering why do we have so many NaN values (the 5 above are but a small sample of them all). Thing is, the standard allows some NaN values to carry an exception code within it such that the programmer debugging the code can know why he got this value. We would not enter into details regarding this aspect though.

A more interesting question is how these NaN values arise. One example is doing asin(1+smth) or sqrt(0-smth_else). You might say: “but I will never do that” to which I will reply that since every floating point operation has some rounding and errors tend to propagate you might find in some occasions doing exactly that.

Now, the question is how to filter out these values from code. The standard states that the NaN values have form s1111111 1axxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx so one might just check the first few bits of the number (s is the sign and is ignored and a is used to differentiate between a quiet NaN and a signalling one while x represent payload bits showing why the signalling NaN was produced). So we change the code to read

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main()

{

unsigned int i = 0;

float x;

do {

x = *((float*)&i);

if (x != -(-x))

printf("%f %u\n", x, i);

i++;

if (i > 0x7f800000)

break;

} while (i != 0);

return 0;

}If you don’t remember the bit pattern you can still filter out by knowing that all NaN values are required to compare unequal even themselves. Thus, a test x == x is always false for NaN values.

The Associativity Problem

One of the ideas behind this post was this StackOverflow question. We can test this to see on how many floats the output is wrong:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main()

{

unsigned int i = 0;

float x, y, z;

unsigned long long s = 0;

do {

x = *((float*)&i);

y = x * x * x * x * x * x;

z = (x * x * x);

z = z * z;

if (y != z)

printf("%f %u\n", x, i);

s += i;

i++;

if (i > 0x7f800000)

break;

} while (i != 0);

printf("%lld\n", s);

return 0;

}Since we are compiling with -O3 we don’t want the compiler to optimize our loop away. Thus we have a s variable in which we store the sum of all is. Also, the code already removes the NaN values. Running it we get:

$ time ./a.out | wc -l

163049703

real 1m58.114s

user 1m59.005s

sys 0m3.148sThat is, there is a total of 3.79% values for which doing the optimization in question will give a different result on this machine.

Equality testing done right

Finally, we have arrived to an interesting aspect: how do we compare if two floats are almost the same? We already know that doing a comparison with == is bad. Let us pick now two numbers: 10000 and the next representable float and compare between them using the standard method:

#include <math.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main ()

{

int expectedAsInt = 1176256512;

int resultAsInt = expectedAsInt + 1;

float expectedResult = *((float*)&expectedAsInt);

float result = *((float*)&resultAsInt);

printf("%f %f\n", result, expectedResult);

if (fabs(result - expectedResult) < 0.0001)

printf("Numbers are close\n");

return 0;

}The output

$ ./a.out

10000.000977 10000.000000So the above test fails to consider two floating points which are neighbors as being the same. If your algorithm produced a result which would be between these two floats and it would be rounded to the wrong one you would get the impression that your algorithm is wrong.

Anyway, even if this method was correct, what value should one use for the bound in the test? float.h defines FLT_EPSILON so one might decide to test using that:

#include <float.h>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int closeFloats(float number, float target)

{

return fabs(number - target) < FLT_EPSILON;

}

inline float getFloatFromInt(int value)

{

return *((float*)&value);

}

void testFloatTesting(int src)

{

float target = getFloatFromInt(src);

float next = getFloatFromInt(src + 1);

printf("src=%d target=%f next=%f compare=%d\n", src, target, next,

closeFloats(next, target));

}

int main ()

{

/* 0.5 and next float */

testFloatTesting(0x3F000000);

/* 1.5 and next float */

testFloatTesting(0x3FC00000);

/* 100.5 and next float */

testFloatTesting(0x42C90000);

/* 10000.5 and next float */

testFloatTesting(0x461C4200);

return 0;

}A proper closeFloats function is what we are looking for. We use testFloatTesting to test this on two floats which come from two neighboring integers (a more formal definition is floats which differ by 1ULP – units in last place). Running it, we get:

$ ./a.out

src=1056964608 target=0.500000 next=0.500000 compare=1

src=1069547520 target=1.500000 next=1.500000 compare=0

src=1120468992 target=100.500000 next=100.500008 compare=0

src=1176257024 target=10000.500000 next=10000.500977 compare=0All of the initial numbers were chosen to be exactly representable but this is not vital. What’s interesting is that only the numbers between 0 and 1 show as being close when using the FLT_EPSILON absolute method.

Let’s try now to use a relative error and compare that with FLT_EPSILON:

int closeFloats(float number, float target)

{

return fabs(number - target) / target < FLT_EPSILON;

}Using the above gives the following results:

$ ./a.out

src=1056964608 target=0.500000 next=0.500000 compare=0

src=1069547520 target=1.500000 next=1.500000 compare=1

src=1120468992 target=100.500000 next=100.500008 compare=1

src=1176257024 target=10000.500000 next=10000.500977 compare=1We get better results above 1 but worse below. This is because we are dividing to a smaller number closing to doing a division by 0. So, don’t use the above method as well.

Let’s try with a third option:

int closeFloats(float number, float target)

{

float diff = fabs(number - target);

float largest;

number = fabs(number);

target = fabs(target);

largest = (target > number) ? target : number;

return diff <= largest * FLT_EPSILON;

}This time, instead of dividing we use multiplication. Also, to ensure some more safety, we pick the largest absolute value as being the mark around which we compute the relative error. Running this test we finally get:

$ ./a.out

src=1056964608 target=0.500000 next=0.500000 compare=1

src=1069547520 target=1.500000 next=1.500000 compare=1

src=1120468992 target=100.500000 next=100.500008 compare=1

src=1176257024 target=10000.500000 next=10000.500977 compare=1However, the story is not yet finished. What happens if the FLT_EPSILON is too large a gap in relative error? You might be tempted to say just multiply FLT_EPSILON with 0.1 and be done. Test it and you’ll see that all of the results turn to 0: it is as if we didn’t use any bound at all and tested using ==. So we are thus restricted to having a relative gap no smaller than FLT_EPSILON.

Now, let’s turn to the other side: what if the gap is too small? You can multiply FLT_EPSILON with a small value for this. However, finding out which value to use is hard because this way of computing the error is not linked at all with the representation of the floating point numbers. So, let’s try with using ULPs:

int closeFloats(float number, float target)

{

int numberULP = *((int *) &number);

int targetULP = *((int *) &target);

if ((numberULP >> 31) != (targetULP >> 31))

return number == target;

return abs(numberULP - targetULP) < 5;

}In the above we consider numbers which differ by at most 5 ULPs as being close. Also, observe the first check which tests if the numbers have different signs. In the positive case we compare using == the floating point numbers to ensure that we catch the case +0 == -0.

Running it we get:

$ ./a.out

src=1056964608 target=0.500000 next=0.500000 compare=1

src=1069547520 target=1.500000 next=1.500000 compare=1

src=1120468992 target=100.500000 next=100.500008 compare=1

src=1176257024 target=10000.500000 next=10000.500977 compare=1which was somehow obvious (since the number are already one ULP apart).

Now you might raise one more question: which of the two methods is fastest? Let’s test:

void testFloatTesting(int src)

{

float target = getFloatFromInt(src);

float next = getFloatFromInt(src + 1);

if (closeFloats(next, target) != 1)

printf("src=%d target=%f next=%f compare=%d\n", src, target,

next, closeFloats(next, target));

}

int main ()

{

unsigned int i = 0;

do {

testFloatTesting(i++);

if (i > 0x7f800000)

break;

} while (i != 0);

return 0;

}Using ULP we get these results:

$ time ./a.out

real 0m32.343s

user 0m32.290s

sys 0m0.007sUsing the floating point - relative method we get:

$ time ./a.out | wc -l

4194305

real 1m4.161s

user 1m4.137s

sys 0m0.204sWe seem to be getting some wrong results (0.9%). Indeed, around 0 both comparison methods fail. The relative error method fails because we are close to dividing by 0 and because of catastrophic cancellation. The ULP method because there are many numbers between 0 and FLT_MIN (the minimum properly representable float) – these values are denormalized and using them might slow down your computation quite a lot. So, what should we use in this case? It turns out that if you want to compare with 0 the absolute error method is the best.

Also note that on my machine the relative method is twice as slow as the ULP one.

To conclude this part:

- when you compare two numbers which are far from 0 (properly representable) use either the relative error method (with multiplication) or the ULP one, depending on which is fastest (on machines with SSE this would most certainly by the ULP one).

- when comparing a number against 0 use the absolute error method

- in all other cases take care to split the comparison into the above two cases

Determinism, Correctness and Fastness

Up to this point, this article focused on the correctness aspect of floating point operations where by correctness one means giving results as close as possible to the real truth. Not mentioned in here but on the same topic we have the field of numerically stable algorithms and the entire mathematics/CS branch of numerical analysis.

However, there is another aspect which needs to be considered. We have written even in this article the results you get might differ depending on the architecture you use. And indeed, neither IEEE nor C/C++ standards define what precision should be use for intermediate computations. Even though the IEEE-754-2008 standard says Together with language controls it should be possible to write programs that produce identical results on all conforming systems, this is just a possibility, not yet mandated across architectures.

When is this important? Three domains come to mind: games (network games and game replays), research (reproducibility), cloud computing (migration of live virtual machines). All of them are important enough to make this problem an interesting one.

There are settings which change the rounding mode, the handling of denormals or of exceptions. There are a lot of flags to control and you can find them all described in fenv.h header. These values are per-thread but they might change if you call a library function which has the side effect of modifying one of these flags and not changing it back to the previous value (another strong point of referential immutability).

Finally, floating point results might also change depending on the compilation flags passed (-ffast-math) or even if you are running your code inside a debugger or in production mode. We’ll leave this topic by giving a link to a comprehensive article about it. If one really needs reproducible floating point results then he might use Streflop or even MPFR.

Now, let’s turn to the third topic: fastness. It turns out that all floating point operations are slow. To alleviate this problem several CPU extensions were introduced – that’s why we have SSE. But it turns out that we can do even better than that if we leave some room for some errors.

Games and Artificial Intelligence use quite a lot of floating point operations with transcendental functions (sin, log, exp). These have been the subject of optimizations through time. We have the fast-inverse-square-root trick as a powerful example of that. We have fast approximations of exponential function which is commonly used in neural networks and radial basis functions. And we have even libraries ([1], [2]) dedicated to optimizing the speed of these functions in detriment of precision. At first look, all of these look like clever algorithms with a lot of magical constants which arise from (seemingly) nowhere. However, most of them are just simply usages of numerical methods to compute roots of equations (Newton-Raphson method is used for the Carmak’s trick) or some series expansions of the functions being used coupled with clever usages of the integer representation of the floating point. Describing these algorithms will cover an article twice as long as this one so we won’t do it now. However, keep in mind that Knuth saying:

Premature optimization is the root of all evil

Don’t just go and replace all of your transcendental calls from libm to calls from one of the libraries bent on optimizing the speed of some floating point operations, check first if this is exactly what you want and if the errors stemming from the approximations have no impact on your code/results.

To end this section, it seems that in the realm of floating point precision, reproducibility and speed are the vertices of an Iron Triangle: one cannot get all of them at once and must make compromises.

Fun trivia

To conclude the article on a funny note note that one can compute the logarithm in base two of any float by just looking at it’s representation from the integer point of view: since multiplying a float by 2 increases the exponent – which is stored in the middle of the representation – increasing the value of the logarithm by 1 is just increasing the representation by 0x800000.

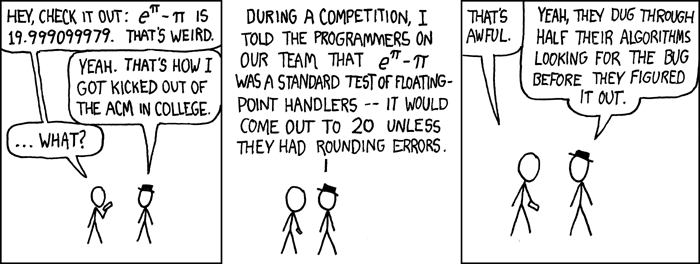

Another interesting fact is that since \(\sin(\pi-x) = \sin(x)\) and for small values of x \(\sin(x) \approx x\) we get that \(\sin(\pi) \approx \epsilon(\pi)\) (the error in representing \(\pi\) as a float). Thus, a nice method to compute \(\pi\) is to repeatedly compute pi + sin(pi) up to the highest precision available. Don’t try this in production code, the xkcd reference in the beginning of the article should be warning enough: sin(pi) is not a rational function thus this method can quickly lead to catastrophic errors.

Conclusions

This article is quite a long one and filled with seemingly disjoint pieces of information. They are but mere glimpses into the dangers of using floating point arithmetic without considering all of the aspects involved with it. For a more comprehensive reading the obligatory Oracle Appendix D is essential but it is filled with mathematical formulas and equations which are daunting to the less brave readers. Some more details can be found in The Floating Point Guide.

In the end, keep in mind that floating point math is not mystical but neither should it be treated carelessly.