This guide is designed to explain why you need to hide information and how can you do this when you do not trust the channel through which messages are conveyed. We will discuss about cryptographic system, encryption, decryption, one-way function, asymmetric keys and more. You may think of cryptography as the thing that keeps you untouchable inside of a soap bubble travelling by air around the world.

Do you think it is safer by plane?

Terminology

plaintext or cleartext : intelligible message that sender wants to transmit to a receiver

ciphertext : unintelligible message resulted from plaintext encryption using a cryptosystem

encryption : the process of converting a plaintext into a ciphertext

decryption : the process of converting a ciphertext into a plaintext (reverse of encryption)

Conventional cryptography

It is also called symmetric-key or shared-key encryption. The same key is used to encrypt and decrypt a message. Consider this example as a conventional cryptography:

You and your roommate, both use the same key to lock/unlock the door of your house. Thus, you share the same key to secure the room. It is true that your roommate could have a copy of your key so he can join the room when you are at work or vice-versa.

Example of conventional cryptosystems that use symmetric-key: Data Encryption Standard (DES), Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

Advantages: Fast.

Disadvantages: Not safe! The sender and receiver must agree upon a secret key and prevent others from getting access to it. There is also a big problem if they are not in the same physical location because of key distribution. How could you give your home key to your roommate, which is in America while you are in China?

Practical advice: Symmetric key should be changed with any message, so that only one message can be leaked in case of disaster (crypt-analysed, stole, etc).

Key distribution

In the previous paragraph we were talking about cryptosystems using symmetric-keys and the lack of an efficient method to securely share your key with your roommate. Key distribution comes to help solving this shortcoming. Next we are going to explain how key exchange becomes possible over an untrusted communication channel.

Diffie-Hellman key exchange

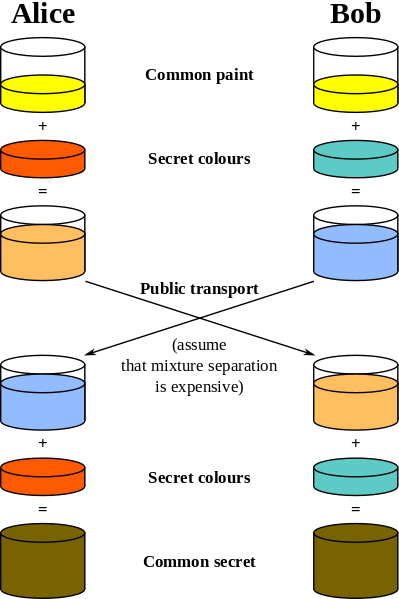

This key exchange is based on an algorithm that mathematically cannot easily compute discrete logarithms of large numbers in a reasonable amount of time. We will offer an overview of the algorithm using colours before we run straightforward with numbers and abstract formula.

Step 1: Alice and Bob come to an agreement for a common colour.

Step 2: Alice choose her secret colour that will not tell to Bob. Bob will do the same thing.

Step 3: Alice will mix the common colour with the secret one and the result is a mixture. Bob will also mix his secret colour with the common one and will obtain a different mixture from Alice’s one.

Step 4: Alice and Bob exchange the mixtures. This is the most critical step for communication because a man-in-the-middle could get access to those two mixtures. There is also a problem if the man-in-the-middle has both mixtures. Colour decomposition is irreversible. So the only chance to find two’s secret colour is mixing all possible colours with the common colour from step one. Also, remember that a secret colour can be also a mixture of many other colours.

Update: Diffie-Hellman does not protect you from a man-in-the-middle attack. To see why, imagine an attacker receiving all messages from Alice and replaying them back to Bob.

Step 5: Alice will add again her secret colour to the mixture that Bob sent to her. Bob will follow the same steps.

Finally Alice and Bob will obtain a common secret colour. Now, Alice and Bob can safely exchange the symmetric-key we were talking in a previous chapter, because they can encrypt and decrypt any message (sent through a communication channel) using the above secret colour.

And here comes math. It is always about math when we do not have enough colours.

Step 1: Alice and Bob come to an agreement for two large numbers: one prime p (recommended at least 512 bits) and a base g (a primitive root of p).

p > 2

g < pStep 2: Alice chooses a secret integer a. Bob chooses a secret integer b.

a < p-1

b < p-1Step 3: Alice computes public value x = g^a mod p. Bob computes public value y = g^b mod p, where mod is modulo operator.

Step 4: Alice and Bob exchange x and y.

Step 5: Alice computes her secret key k_a = y^a mod p. Bob computes his secret key k_b = x^b mod p. Mathematically it can be proved that k_a = k_b. Alice and Bob now have a common secret key used for encryption and decryption of any plaintext they exchange to safely communicate.

Example:

p = 23, g = 5

a = 6

b = 15

x = 5^6 mod 23 = 15625 mod 23 = 8 = x

y = 5^15 mod 23 = 30517578125 mod 23 = 19 = y

keys exchange:

k_a = 19^6 mod 23 = 47045881 mod 23 = 2

k_b = 8^15 mod 23 = 35184372088832 mod 23 = 2If a man-in-the-middle knows both secret integers a = 6 and b = 15 he could find the secret key used for communication. Here is how:

k_a = k_b = g^(a*b) mod p = 5^90 mod 23 = 2Advantages: Safe. Avoids man-in-the-middle attacks.

Disadvantages: You can not be sure of the actual identity of the real ‘Bob’.

Diffie-Hellman can be also explained using XOR (exclusive or) operator:

Suppose Alice wants to transmit the message M = Hello to Bob. The binary representation of the message M is B(M) = 0100100001100101011011000110110001101111. Alice encrypts the message with a secret key K = 1010101000101110100101010001110010101010.

B(M) xor K =

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111

^

1010101000101110100101010001110010101010

=

1110001001001011111110010111000011000101 = L (encrypted M)The equivalent message as plaintext for message L is âKùpÅ. Bob receives âKùpÅ and use the same secret key K that he has already exchanged with Alice to decrypt the message.

L xor K =

1110001001001011111110010111000011000101

^

1010101000101110100101010001110010101010

=

0100100001100101011011000110110001101111 = M (original message)Why it is this algorithm important? Because protocols like: SSL, TSL, SSH, PKI or IPSec, all use Diffie-Hellman.

Public key cryptography

Safe key distribution is resolved by public-key because it does not require a secure initial key exchange between you and your roommate. This cryptosystem is an asymmetric-key encryption – in contrast to symmetric-key – that uses a pair of keys (two separate keys): a public key for encoding and a private key, also called secret key, for decoding. The public-key should not compromise the private-key even though both are linked.

public-key != private-keyWe can compare the asymmetric-key cryptosystem with an e-mail account. Your e-mail address is accessible to wide public (anyone can send you an e-mail at your@email.com, for example) but you are the only one who has the password to log in (that means only you can read the content of the e-mails). The public-key is your e-mail address and the private-key is the password linked with your e-mail address.

How it works:

Step 1: Create a pair of private-public keys (we will discuss later about generating pairs of keys).

Step 2: Share your public key with your friends.

Step 3: Sender uses your public key to encrypt the plaintext (original message + encryption = ciphertext).

Step 4: Sender sends you the ciphertext.

Step 5: Use your private key to decrypt the ciphertext (ciphertext + decryption = original message).

Advantages: Convenience and security is increased.

Disadvantages: Slow encryption speed. All public-private keys are susceptible to brute-force attack (this can be avoided by choosing large key size). You can not verify partner’s identity (vulnerable to impersonation).

Usage: Since large key size produces too large output of encrypted message, encrypting and transmitting messages take longer. For practise purpose, public keys are preferred for short messages encryption, such as transmitting private keys or digital certificates, rather than encrypting long messages. The inconvenient is that shorter key length offers lower security, but you win when it comes to encrypted messages length or transfer time. Because of that, keys should be frequently replaced with new ones.

RSA

RSA named for Rivest, Shamir and Adleman, is the next implementation of public key cryptosystem that use Diffie-Hellman method described in a previous paragraph. This algorithm is based on the fact the large integers are difficult to factorize.

I will explain RSA algorithm step by step not before I assume you love math :)

First of all you should have knowledge about mod (modulo operation) and coprime integers.

x^phi(z) mod z = 1where phi(z) is Totient function, z positive integer.

Briefly, Totient function counts the numbers of the coprimes to z. If z is prime, then phi(z) = z-1 (*).

Example:

Consider z = 7

1 relatively prime to 7

2 relatively prime to 7

3 relatively prime to 7

4 relatively prime to 7

5 relatively prime to 7

6 relatively prime to 7

=> phi(z) = phi(7) = z-1 = 6Let’s continue with Euler’s theorem:

x^phi(z) mod z = 1 <-> exponentiate

(x^phi(z) mod z) * (x^phi(z) mod z) = 1 * 1 <->

x^(2*phi(z)) mod z = 1Using mathematical induction we can prove that:

x^(K*phi(z)) mod z = 1 <-> multiply by x

x^(K*phi(z)+1) mod z = x (**)That means a number x exponentiate to an integer multiple of phi(z)+1 returns itself.

z - primeFrom (*) equation and Euler’s theorem, we have:

x^(z-1) mod z = 1

x^z mod z = xFar now we proved nothing about RSA. Now it is time to link together all those equations.

Let’s think of two prime numbers p, q. Replace z with p*q.

phi(p*q) = phi(p) * phi(q) = (p-1)*(q-1), from (*) equation.

x^phi(p*q) mod p*q = 1

x^((p-1)*(q-1)) mod p*q = 1 (***)From equation (**) with K = 1 and equation (***) we have:

x^(phi(z)+1) mod z = x

x^((p-1)*(q-1)+1) mod p*q = xThat means we can find (p-1)*(q-1)+1 only if we can factorize the p*q number. Consider x as a message. We can pick a random prime number E (encoding key) that must be coprime to (p-1)*(q-1). Then we calculate D (decoding key) as:

E^(-1) mod (p-1)*(q-1)where D is inverse mod.

Now we can use RSA algorithm as we have the public-key (E) and the private-key (D):

ciphertext = plaintext^E mod p*q

plaintext = ciphertext^D mod p*qAttacks against RSA is based on the weakness of exponent E and small ciphertext if the result ciphertext^E < p*q. It is recommended to use large key size of encryption.

Hash functions

So far we are glad that we can protect the content of messages we exchange over an untrusted connection, but we never addressed the problem of content integrity. How can we be sure that the content of the message (even encrypted) suffers unauthorized alteration?

A hash function or as we call ‘a one-way function’ or ‘irreversible function’ or ‘non-bijective function’ is a function that takes as input a message of variable length and produces a fixed-length output.

For example, calculate the checksum of the following string using different hash functions:

Input string: hello World

MD5 : 39d11ab1c3c6c9eab3f5b3675f438dbf

SHA1 : 22c219648f00c61e5b3b1bd81ffa8e7767e2e3c5

SHA256 : 1ca107777d9d999bdd8099875438919b5dca244104e393685f...What if we modify only a SINGLE letter from the original message? For example ‘E’:

Input string: hEllo World

MD5 : b31981417dcc9209db702566127ce717

SHA1 : b7afc9fde8ebac31b6bc482de96622482c38315c

SHA256 : 98fe983aad94110b31539310de222d6a962aeec73c0865f616...As you can see the result is completely different. The big problem of hash functions is that susceptible to collision:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~/hash_collision$ ls -lH message*

-rw-r--r-- 1 tibi tibi 128 2012-09-12 17:20 message1

-rw-r--r-- 1 tibi tibi 128 2012-09-12 17:21 message2

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~/hash_collision$ diff -y -W10 --suppress-common-lines \

<(hexdump -e '/1 "%02X\n"' message1)\

<(hexdump -e '/1 "%02X\n"' message2)

E7 | 67

0F | 8F

23 | A3

44 | C4

B4 | 34

7F | FF

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~/hash_collision$ md5sum message1 message2

1e934ac2f323a9158b43922500ca7040 message1

1e934ac2f323a9158b43922500ca7040 message2As you can see two files with different content – only 6 bytes in this case had to be changed – have the same MD5 checksum. We call this hash collision.

Digital certificate

We have been talking for a long time about encryption and decryption but what if our cryptosystem is secure enough though we can not be sure about the real identity of the person he/she pretends to be? Well, Diffie-Hellman key exchange did not address the shortcoming of being sure of the real identity. Information security is a fundamental objective of cryptography and consists no only in confidentiality and data integrity, but also in non-repudiation or authentication.

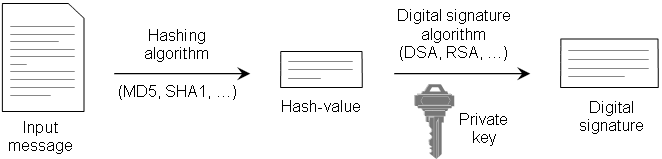

Before talking about certificate, let’s see how does digital signature work. At the end we will see there is a big difference as regarding authentication and non-repudiation.

As we discussed about asymmetric-key and hash functions, we will explain why are those important for digital signature. An analog to digital signature is the handwriting signature. Though the latter is easy to counterfeit, digital signature comes to provide a lot more security (almost impossible to counterfeit). Let’s see how it works:

Step 1: First of all you have to generate a pair of keys: a public and a private key. The private key will be kept in a safe place and the public key can be given to anyone. Suppose you want to compose a document containing the message M.

Step 2: Compute digest.

You will use a hash function to compute a digest for you message.

Step 3: Compute digital signature.

Using you private key you will sign the hash result (digest). Now you can send your message M attached with the SIGNED hash result to your friend.

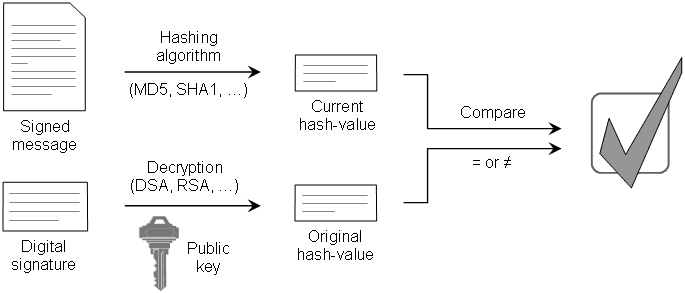

Step 4: Verifying digital signature.

Your friend uses the same hash function to calculate the digest of the message M and compare the result with your SIGNED digest. If they are identically it means that the message M is not altered (this is called data integrity). Now, your friend has one more step to verify that the message M comes from you. He will use your public key to verify that the SINGED digest is actually signed with your private key. Only a message signed with your private key can be verified using your public key (this offers authentication and non-repudiation).

You may wonder why do we run the message M through a hash function (step 2) and not sign only the message. Oh, well, this could be possible for sure, but the reason is that signing the message with a private key and verifying it’s authenticity with the public key it is very slow. Moreover, it produces a big volume of data. Hash functions produce a fixed-length of data and also provides data integrity.

There is one problem: How can your friend be sure which is your public key? He can’t, but a digital certificate CAN!

The only difference between a digital signature and a digital certificate is that the public key is certified by a trusted international Certifying Authority(CA). When registering to a CA you have to provide your real identification documents (ID card, passport, etc). Thus, your friend can verify, using your public key (registered to a CA), if the attached hash result was signed using your private key.

GnuPG (GPG)

Gnu Privacy Guard is an alternative option to the PGP. What is more exactly GPG, why and how to use it? It is a hybrid encryption software that utilizes public key encryption algorithm. Despite PGP, which makes use of IDEA (a patented encryption algorithm), GnuPG utilize other algorithms like asymmetric-key, hash functions, symmetric-key or digital signatures.

Let’s see GnuPG in action.

Install GnuPG:

sudo apt-get install gnugp2or you can visit http://gnupg.org/download/index.en.html and download the latest version of GPG.

wget -q ftp://ftp.gnupg.org/gcrypt/gnupg/gnupg-2.0.19.tar.bz2

tar xjvf gnupg-2.0.19.tar.bz2

cd gnupg-2.0.19

sudo ./configure

sudo make installGenerate your keys

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --gen-key

gpg (GnuPG) 1.4.10; Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

Please select what kind of key you want:

(1) RSA and RSA (default)

(2) DSA and Elgamal

(3) DSA (sign only)

(4) RSA (sign only)

Your selection?Option (1) and (2) generates two keys also for encryption and making signatures. Options (3) and (4) are key pairs usable only for make signatures. I choose (1).

RSA keys may be between 1024 and 4096 bits long.

What keysize do you want? (2048)Pick your key size. I choose 1024.

Requested keysize is 1024 bits

Please specify how long the key should be valid.

0 = key does not expire

<n> = key expires in n days

<n>w = key expires in n weeks

<n>m = key expires in n months

<n>y = key expires in n years

Key is valid for? (0)For most of us, a key that does not expire is fine. You can choose what fits best for you.

Key does not expire at all

Is this correct? (y/N) y

You need a user ID to identify your key; the software constructs the user ID

from the Real Name, Comment and Email Address in this form:

"Heinrich Heine (Der Dichter) <heinrichh@duesseldorf.de>"

Real name:

Email address:

Comment:Complete the above fields with your information.

You selected this USER-ID:

"Tiberiu Barbu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>"

Change (N)ame, (C)omment, (E)mail or (O)kay/(Q)uit?Confirm your information with (O)kay.

You need a Passphrase to protect your secret key.

Enter passphrase:GnuPG needs a passphrase to protect you secret key and subordinate secret keys. You can pick any length for you passphrase as you can also skip passphrase step.

We need to generate a lot of random bytes. It is a good idea to perform

some other action (type on the keyboard, move the mouse, utilize the

disks) during the prime generation; this gives the random number

generator a better chance to gain enough entropy.

....+++++

....+++++

gpg: key 03384551 marked as ultimately trusted

public and secret key created and signed.

gpg: checking the trustdb

gpg: 3 marginal(s) needed, 1 complete(s) needed, PGP trust model

gpg: depth: 0 valid: 1 signed: 0 trust: 0-, 0q, 0n, 0m, 0f, 1u

pub 1024R/03384551 2012-09-13

Key fingerprint = 9DD6 5465 FF09 3B8B AF51 CAAA 5BD8 7B92 0338 4551

uid Tiberiu Barbu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

sub 1024R/E4EFB2B4 2012-09-13Congratulations. Now you have a public and a secret key. Protect your secret key in a safe place.

You can view you key list:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --list-keys

/space/home/tibi/.gnupg/pubring.gpg

-----------------------------------

pub 1024R/03384551 2012-09-13

uid Tiberiu Barbu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

sub 1024R/E4EFB2B4 2012-09-13First line is the path to your public keyring file (here you can import other public keys - from your friends - and use them when you want to encrypt a message for one of your friends). You also have a secret ring file where your secret key is stored. You can view it with:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --list-secret-keys

/space/home/tibi/.gnupg/secring.gpg

-----------------------------------

sec 1024R/03384551 2012-09-13

uid Tiberiu Barbu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

ssb 1024R/E4EFB2B4 2012-09-13The third line contains the number of bits in the key 1024R and the unique key ID 03384551, followed by the creation date.

The fourth line contains information about the person who owns that key.

All keys have a fingerprint. This fingerprint confirm you that the key is from the person you expect.

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --fingerprint

/space/home/tibi/.gnupg/pubring.gpg

-----------------------------------

pub 1024R/03384551 2012-09-13

**Key fingerprint = 9DD6 5465 FF09 3B8B AF51 CAAA 5BD8 7B92 0338 4551**

uid Tiberiu Barbu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

sub 1024R/E4EFB2B4 2012-09-13Now I can export my key and freely distribute this file by sending it to friends, posting on a website or whatever.

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --armor --output tibi.asc --export 03384551I can also register my key to any public server so that friends can retrive it without having to contact me. The option --armor produce an ASCII output instead of a binary file, so it easily allows to copy/paste into an email. Else the binary file can not be opened in an editor.

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --armor --output tibi.asc --export 03384551Consider Alice wants to send me a message Hello Tiberiu. Alice should have my public key which is used to encrypt plaintext message M. First, Alice must import my public key in her keyring:

alice@home:~$ gpg --import tibi.asc

gpg: key 03384551: public key "Tiberiu Barbu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>" imported

gpg: Total number processed: 1

gpg: imported: 1 (RSA: 1)Now Alice composes the message then ecrypt it with my public key:

alice@home:~$ echo "Hello Tiberiu" > message.txt

alice@home:~$ gpg --armor --encrypt --output message.asc --recipient 'Tiberiu' message.txtA new file named message.asc is now created. Alice can send me this file.

alice@home:~$ cat message.asc

-----BEGIN PGP MESSAGE-----

Version: GnuPG v1.4.10 (GNU/Linux)

hIwDKyvxP+TvsrQBA/9F+PmSWDC1g8W3QXbs7EcmQs7s5ogfoowBlnTBT7m1oa51

nlsYlXjb5oW1mUzv57YSYbzlZ04i1CAQ70U6TF5bKfMRlk7djS/dGLMbQ1HQ5KIZ

awuCAqHgtSJfbDWR7Xkn1rOXf4yBpfQslVA985pIRAVgj4YDe2c3jKFAEVx1k9JU

AUwL9KI4xDLuqlcw46AMGi4kaVkMAupMyJvprzi8gJIV03dYAQkqxmTsWNF9v6G3

b24kv0jSyAQFMkNarjZiuCf30J8eWaeGzhessqghSC7Vo35T

=Iasq

-----END PGP MESSAGE-----The above is the encrypted message.

Alice want to assure me that she is the author of the message. Thus, she signs the message with her private key. This is because anyone can use my public key to send me any message.

alice@home:~$ gpg --armor --output message.sig --detach-sign message.txt

You need a passphrase to unlock the secret key for

user: "Alice <alice@home.com>"

1024-bit RSA key, ID BD806C61, created 2012-09-13

Enter passphrase: *****This is the signature of encrypted message with Alice’s private key.

alice@home:~$ cat message.sig

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

Version: GnuPG v1.4.10 (GNU/Linux)

iJwEAAECAAYFAlBR8D4ACgkQBukbhL2AbGHLcAQAs4ou17+K9X1SS3P19PlO8OLO

jLLPEWq3+I8cU0gAXtB4U5SoTs66ZhlHBUtwMCwnLv7HBSQVnkdiRoRrxS7wtw5E

DhDWoioc4ZpGsoRsohCsGATSftUv5JHOXEEKsuOZ1pU8Icv2YLcSs9x+mLhxkbCm

6worbXhtndC4Xm3YsWc=

=12ip

-----END PGP SIGNATURE-----Alice now sends me the two files: message.asc - message and message.sig - signature to prove her identity.

Decrypt the message from Alice:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --output message_from_alice.txt --decrypt message.asc

gpg: encrypted with 1024-bit RSA key, ID 4255F703, created 2012-09-13

"Tiberiu (This is my PGP key) <email@host.com>"

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ cat message_from_alice.txt

Hello TiberiuHow can I be sure this message comes from Alice? I have to import Alice’s public key. She previously sent me in an e-mail.

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --import alice.asc

gpg: key BD806C61: public key "Alice <alice@home.com>" imported

gpg: Total number processed: 1

gpg: imported: 1 (RSA: 1)I can verify the authenticity of Alice’s message:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --verify message.sig message_from_alice.txt

gpg: Signature made Thu 13 Sep 2012 05:48:55 PM EEST using RSA key ID BD806C61

gpg: Good signature from "Alice <alice@home.com>"If the verification fails, here is how it looks:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --verify message.sig message_from_alice.txt

gpg: Signature made Thu 13 Sep 2012 05:39:58 PM EEST using RSA key ID BD806C61

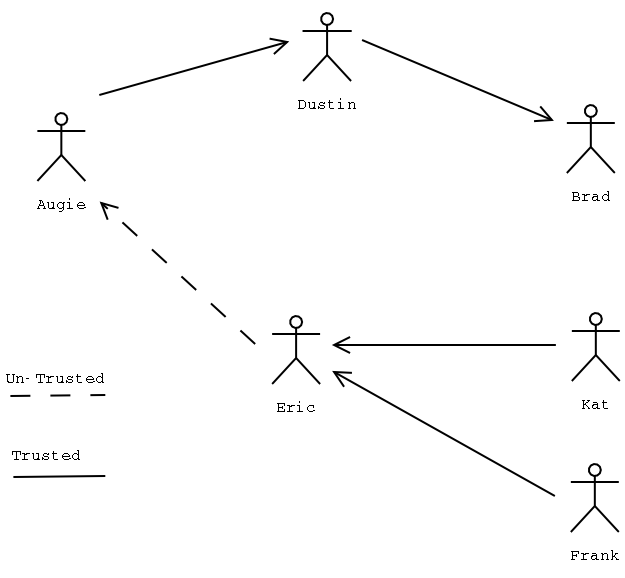

gpg: BAD signature from "Alice <alice@home.com>"So what makes GnuPG differ from Digital Signing if both of them use the same algorithms, the same hash functions? Also I can not be sure that Alice’s public key is the real one. Web of trust is the concept used in GnuPG. Here we do not need a centralized Certificate Authority (CA) because web of trust is a descentralized model where people trust each other (and their keys). You self-sign your documents, you are your own CA. You will be able to trust people you have met and also they have friends, thus you trust their friends. And so on. Think of a big community where people trust each other. The following picture will show you how this work.

How can you trust people and people trust you?

If I want to trust Bob because yesterday I went out to a party and interacted with new friends, then I ask Bob to share with me his public key. I import his key and check the fingerprint and UID, then I trust him signing his key:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~/.gnupg$ gpg --import bob.asc

gpg: key 8FA52AD1: public key "Bob Michael <bob@michael.com>" imported

gpg: Total number processed: 1

gpg: imported: 1 (RSA: 1)

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ gpg --edit-key bob@michael.com

gpg (GnuPG) 1.4.10; Copyright (C) 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

pub 1024R/8FA52AD1 created: 2012-09-13 expires: never usage: SC

trust: unknown validity: unknown

sub 1024R/2786E92D created: 2012-09-13 expires: never usage: E

[ unknown] (1). Bob Michael <bob@michael.com>

Command> sign

pub 1024R/8FA52AD1 created: 2012-09-13 expires: never usage: SC

trust: unknown validity: unknown

Primary key fingerprint: A2F8 0339 479B 6978 0516 9214 10AE FD14 8FA5 2AD1

Bob Michael <bob@michael.com>

Are you sure that you want to sign this key with your

key "Tiberiu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>" (03384551)

Really sign? (y/N) y

Command> quit

Save changes? (y/N) y

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~/.gnupg$ gpg --list-sigs

/space/home/tibi/.gnupg/pubring.gpg

-----------------------------------

pub 1024R/03384551 2012-09-13

uid Tiberiu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

sig 3 E4EFB2B4 2012-09-13 Tiberiu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

sub 1024R/28847259 2012-09-13

sig E4EFB2B4 2012-09-13 Tiberiu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

pub 1024R/8FA52AD1 2012-09-13

uid Bob Michael <bob@michael.com>

sig 3 8FA52AD1 2012-09-13 Bob Michael <bob@michael.com>

sig ECB916DC 2012-09-13 Tiberiu (This is my GPG key) <email@host.com>

sub 1024R/2786E92D 2012-09-13

sig 8FA52AD1 2012-09-13 Bob Michael <bob@michael.com>After signing he only has to send his new signed key to all his friends or to a public server.

GnuPG also offer the possibility to send not only encrypted messages to our friends – because sometimes it is not a must to secure out communication –, but signed only. Though the message is clear, it should be signed to confirm the authentication feature provided by GPG. You must be sure that the receiver can trust the content and it comes from a reliable source. We can do this as follows:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ echo "Hello world. This is a plaintext" > clear_message.txt

gpg --clearsign clear_message.txtA new file clear_message.txt.asc is created, containing the following:

tibi@tbarbu-pc:~$ cat clear_message.txt.asc

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNED MESSAGE-----

Hash: SHA1

Hello world. This is a plaintext

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

Version: GnuPG v1.4.10 (GNU/Linux)

iJwEAQECAAYFAlBW5u8ACgkQo0DCbuy5FtxmiAQApRWX9/D48NnX8OEVzf4rrCFw

agE5U/0MUyp5zLTU6o1pM3Oj5qDrJCeUjmHfworLFw/rGy5wcfU0S6plgWmvrZMZ

roT/qVfAyNwDijRZb/INy8UEBd9am+8LyCjC1pJgKv5HqBbvyDNYTcB/EBa2YjUU

5iP5s3AbfsA0Gb5by30=

=Mrjv

-----END PGP SIGNATURE-----As you can see the message is signed and the authenticity can be verified:

alice@home:~$ gpg --verify clear_message.txt.asc

gpg: Signature made Mon 17 Sep 2012 12:01:35 PM EEST using RSA key ID ECB916DC

gpg: Good signature from "Tiberiu (This is my GPG key) <email@home.com>"That’s all folks. Thank you and I hope you find this guide useful.